Relationship between Amp and Runs

In this article, we analyze the relationship between the measure of disorder \(\mathit{Amp}\), which I introduced a while ago, and the classic measure of presortedness \(\mathit{Runs}\), the number of ascending runs in a sequence.

Identity of \(\mathit{Runs}\)

\(\mathit{Runs}\) is probably one of the oldest measures of disorder of interest, both for its conceptual simplicity, ease of computation, and direct application to sorting. It counts the number of ascending “runs” in a sequence, that is, the number of already sorted subsequences of adjacent elements. Natural mergesorts such as timsort explicity looks for existing runs in a sequence, and are adaptive with regard to the number of runs.

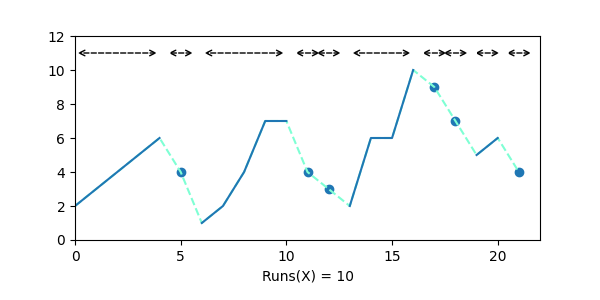

In the illustration above, the full blue lines represent runs, and the blue dots represent runs of size 1.

It is pretty obvious that \(\mathit{Runs}\) as defined above returns \(1\) for a sorted sequence, a property that quickly became a problem when Heikki Mannila standardized the concept of measures of presortedness, requiring that they return \(0\) for a sorted sequence. To circumvent that issue, \(\mathit{Runs}\) is often defined in the literature as “the number of ascending runs in a sequence, minus \(1\)”, a definition that satisfies all of the axioms required for a measure of presortedness. As a matter of fact, this is the definition that we will be using in the rest of this article.

Another way to look at this “minus one” trick is to considers that \(\mathit{Runs}\) counts the number of steps-down in the sequence, where a step-down corresponds to a point in the sequence where an element compares smaller than its preceding neighbor (the dashed aquamarine lines in the illustration above). It is trivial to see that it does indeed correspond to the number of runs minus \(1\).

The literature around measures of disorder mostly analyzes them over sequence of distinct elements. In this article, we also consider sequences where elements can compare equivalent, for which we keep the “step-down” definition of \(\mathit{Runs}\). It technically means that the runs we are considering are non-decreasing sequences of adjacent elements.

\(\mathit{Amp}\) and steps-down

I am not going to repeat the definition of \(\mathit{Amp}\) here, because doing so for every new article would be bothersome. If you found this note without having heard of it before, you can refer to the article linked in the introduction.

When comparing \(\mathit{Amp}\) and \(\mathit{Runs}\), the first thing that stands out is that the former finds presortedness in a descending sequence, while the latter does not. In fact, \(\mathit{Runs}(X)\) returns \(\lvert X \rvert - 1\) when \(X\) is sorted in reverse order, which is the highest possible value it can take. This is in stark contrast with \(\mathit{Amp}(X)\) which finds \(0\) for the same \(X\). This first observation leads to the following result:

There is no constant \(c \in \mathbb{R}\) such as \(\mathit{Runs}(X) \le c \cdot \mathit{Amp}(X)\) for every sequence \(X\).

…and naturally to a follow-up question: is there a constant \(c \in \mathbb{R}\) such as \(\mathit{Amp}(X) \le c \cdot \mathit{Runs}(X)\) for every sequence \(X\)?

It is not immediately obvious however how steps-down contribute to disorder in \(\mathit{Amp}\). We can try to build an initial intuition by looking at a few distributions:

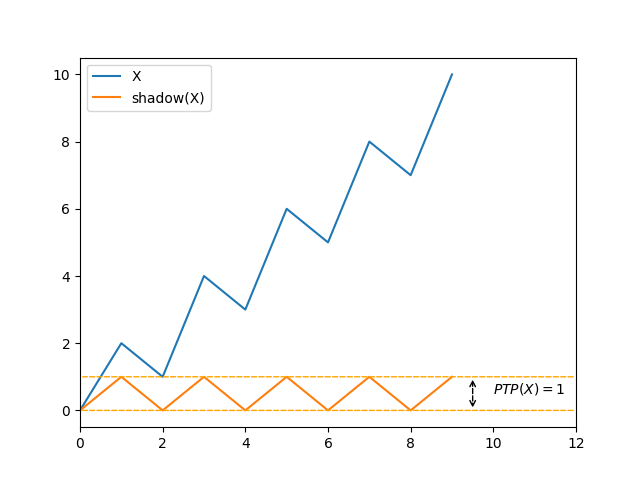

- \(\mathit{Amp}(X) = 0\) when there is no step-down in \(X\).

- \(\mathit{Amp}(X) = 0\) when there is only steps-down in \(X\).

- \(\mathit{Amp}(X) = \lvert X \rvert - 2\) when the result of pairwise comparisons changes at each step (\(\frac{\lvert X \rvert}{2}\) steps-down).

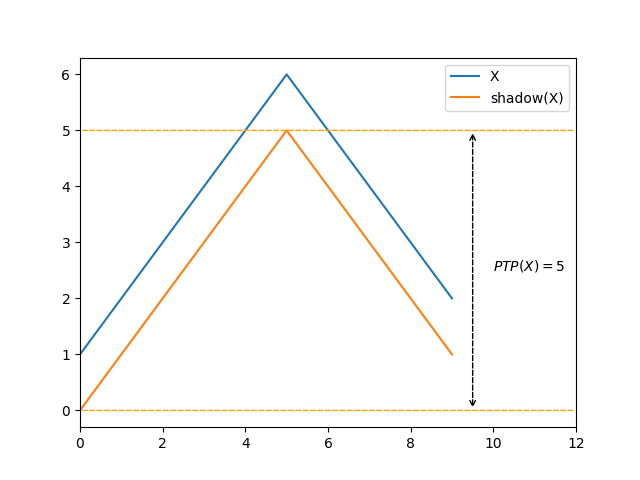

Those special cases might suggest that the value of \(\mathit{Amp}\) is directly linked to the difference between its number of steps-down and steps-up, though this is easily disproven with the following example that has the same number of steps-up and steps-down as the previous one:

An interesting observation about \(\mathit{Amp}\)’s worst case is that it also isn’t a low-disorder case for \(\mathit{Runs}\). In that specific case we have \(\mathit{Amp}(X) = 8\) and \(\mathit{Runs}(X) = 5\), which suggests a conjecture of \(\mathit{Amp}(X) \le 2 \mathit{Runs}(X)\).

To approach the problem, we are going to analyze how much turning a single step-up into a step-down can affect the result of \(\mathit{Amp}\). The reasoning is as follows: \(\mathit{Runs}\) grows by \(1\) for every step-down in the sequence, therefore if \(\mathit{Amp}\) grows by at most some constant \(c\) for every such step-down, then we can conclude that \(\mathit{Amp}(X) \le c \cdot \mathit{Runs}(X)\) for every sequence \(X\).

Let’s go back to the original definition of \(\mathit{Amp}\):

- A step-up corresponds to a \(1\) in the pairwise order.

- A step-down corresponds to a \(-1\) in the pairwise order.

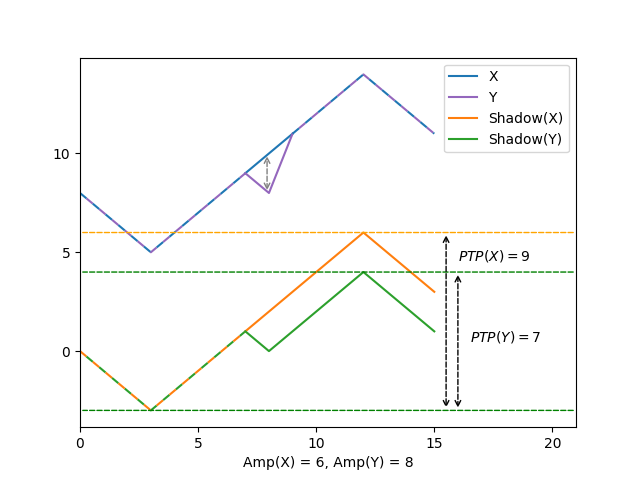

Turning a step-up into a step-down therefore amounts to retrieving \(2\) from every subsequent element of the prefix sum (the shadow). This does not change the size of the sequence, nor the number of equivalent elements, so we only need to check how it affects the peak-to-peak amplitude of the shadow, which is the absolute difference between its extrema.

The maximum disorder that the proposed swap can introduce is when the minimum of the shadow is on the left of the changed element, and the maximum of the shadow on its right. In such a scenario, \(2\) will be retrieved from the maximum of the shadow, while the minimum will remained unchanged, leading to a net reduction of \(2\) from the \(\mathit{PTP}\).

For a given input size, the value of \(Amp\) increases as much as \(\mathit{PTP}\) decreases as long as we are dealing with a sequence of distinct elements. It follows that a step-down can introduce no more than \(2\) units of disorder in \(\mathit{Amp}\), which allows use to validate the original conjecture that \(c = 2\), and to conclude by validating the following relationship:

\[\mathit{Amp}(X) \le 2 \mathit{Runs}(X)\]While a nice stepping stone, it feels like this result only tells a part of the whole story: my gut feeling is that there is much more to be said about the relationship between \(\mathit{Amp}\) and \(\mathit{Runs}\). I plan to revisit it in the future, be it only to properly analyze where \(\mathit{Amp}\) sits in the partial ordering of measures of disorder.